“(…) in an increasingly global marketplace, understanding and catering for difference is crucial to business success. The design challenge is to include and not exclude unknowingly.” [1.]

Trying to understand any theory or concept, whether design related or not, it makes sense to start with its origins. The thoughts and considerations that form the backbone of inclusive design date back to the 1960s. It was then designers began to learn of their influential role and the concomitant responsibility of their actions within culture. One can say that numerous design considerations such as sustainability, social responsibility and consumerism root from the thought process during that time.

There were several factors that led to the emergence of inclusive design. One of them was the ‘Normalisation Principle’, which emerged from Scandinavia in the late 1960s. Bengt Nirje, who was the executive director at the ‘Swedish Association for the Developmentally Disturbed’ was working on a new Swedish law at the time with the aim to create ‘normal’ living conditions for people with disabilities instead of forcing them to live in institutions and asylums causing isolation. [2.]

In its origin the ‘Normalisation Principle’ was mostly applied to people with a mental disability, but Nirje later redefined it as:

“Making available to all persons with intellectual disability or other handicaps, patterns of life and conditions of everyday living which are as close as possible to or indeed the same as the regular circumstances and ways of life in society.” [3.]

Another factor was the previously discussed social model of disability. It was also part of the considerations and new concepts developed in Scandinavia and led to the believe that “the environment, not necessarily the individual needs to change.” This stemmed from the fact that “consumers – people with disabilities – are demanding the right to live in the community, with their disabilities, on the same basis as others. They are demanding a society that allows them to be themselves, like other people, and which accommodates their disabilities and special needs. They are demanding a society in which all public facilities and opportunities are accessible to them and appropriate for their needs and abilities.“ [4.]

Amongst a few others, one particular person – Victor Papanek – started to discuss and formulate these new and arising concepts in the 1970s. He worked with the Swedish government in their ‘normalisation’ phase of closing down institutions and accommodating disabled people among communities and in accessible housing.

The book ‘Design for the Real World’ is a manifest of his pioneering work, establishing the foundation and inspiration for many of today’s key thinkers within the field of inclusive design.

Throughout numerous case studies within the first chapters of his book, Papanek points out that not only products or services aimed at specialist user groups, but also those with a larger target audience have great implications on the consumers life. This type of analysis and the problems addressed are fundamental considerations in todays’ product development cycles but were not before considered on a wider scale.

Using multiple examples Papanek sets out observing consumer behaviours, problems encountered, related health implications, accessibility and the lack of consideration for improvement. [5.]

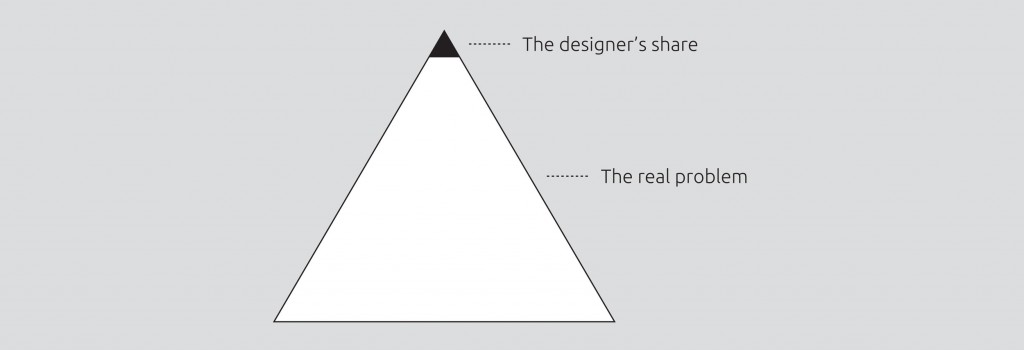

Looking at the way designers usually approach and are involved in the development process of a product or service, Papanek introduces a simple diagram visualising the design problem.

This diagram [6.] effectively depicts the problem and illustrates the main reason how user groups are unknowingly being excluded from the majority of design applications.

Instead of engaging with the actual design problem and finding solutions for it, designers disregard or simply don’t understand user needs and the difficulties encountered. It is every designer’s obligation and responsibility to question any product they are asked to design and engage with the design problem in its entirety.

Approaching the design problem from the bottom of the pyramid is the key element to start developing user-centred and truly inclusive design solutions.

In order to understand and successfully address user needs, a closer look at the relevant target audience is necessary. Inclusive design is often associated with accessibility and the catering for users with special needs – when in fact it is a concept to establish solutions usable to as many as possible – or more importantly one that does not exclude anyone from usage without consideration.

Most users – will at one point in their life if not permanently – experience some sort of impairment or disability that causes them difficulty when interacting with their environment.

In 1982 Papanek held a keynote speech at the first international ‘Coalition for a Barrier-Free Environment’ conference with the ‘United Nations’ in New York. He summarises that he was very pleased to see that most of the other speakers addressed the idea of seeing society as a whole instead of addressing all the ‘minorities’ it is made up from individually. [7.]

Considering who many of these so-called ‘minorities’ are, it soon becomes obvious that catering for their needs will establish design for the mainstream market and general public after all.

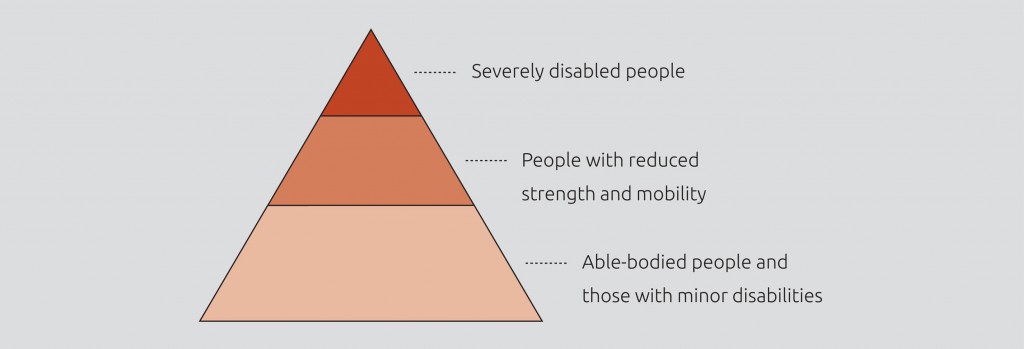

Dividing users in terms of their degree of impairment the user pyramid or so called ‘pyramid of needs’ is formed. It was developed by Maria Benktzon after a workshop with Papanek and with the support of the Swedish welfare board.

“The pyramid helps identify groups with capabilities that challenge and extend the interpretation of the design brief {…}”. [8.]

Most commonly this pyramid[9.] is approached from the bottom up.[10.] This creates mainstream solutions with the possibility of reaching a large market share from the start. The problem with this solution however is that consideration often ends after catering for the needs of the able-bodied and general public. The number of people that are being included additionally moving up the pyramid diminishes and most commonly marketers interpret that as a sign of slowdown in product success resulting in the stop of further consideration and development. Creating solutions usable to some of the upper parts of the pyramid is often coincidental rather than considered.

Approaching the pyramid from the top down is the key for creating truly inclusive design solutions.[11.] By catering for the requirements of those most in need of consideration first, products and services can – if this approach is well executed – become available for user groups outside the original target market and the general public.

Evaluating the user pyramid further it is very interesting to find out who the different parts consist of. The minor disabilities group could be those with slight visual impairments, learning difficulties or people affected by temporary illness. Reduced strength and mobility might be caused by the effects of pregnancy, an accident resulting in a broken bone or progressing age. Severe disabilities don’t have to be present from birth; they could be the result of an infection or accident amongst other reasons.

Regardless of the reason for the impairments users face, it is a fact that every person in their life requires education, medical assistance, transportation or other means that in some way or another give them special needs. The dynamics within the user pyramid are therefore constantly shifting and people who are completely able-bodied might find themselves confronted with difficulties moving them into a different category one day.

This proves that inclusive design is not about generating solutions for ‘minorities’ or niche markets after all – but design for as wide of an audience as possible.

Additional Reading

There are numerous design theories and movements around the world that show similarities to inclusive design. Most books on the topic make reference to these and it is therefore useful to give a short impression of their outlines: [12.] [13.]

- Design For All – Movement in Scandinavia relating to their social democratic principles of a fair society for all. Much alike the universal design concept but with a focus for information on communication technology.

- Transgenerational Design – Focuses on exclusion because of age and less on disability. Further a more market-led approach following studies of age shift in society.

- Universal Design – The concept is to enable universal access to public and private environments. It originated in America. At the core of the universal design theory are its seven principles:

- Equitable use,

- Flexibility in use,

- Simple & intuitive,

- Perceptible information,

- Tolerance for error,

- Low physical effort,

- Size/Space for approach & use

Further these are some of the key thinkers and institutions within the field of inclusive design:

- Roger Coleman – Is one of the co-founders of the ‘Helen Hamlyn Research Centre’ and used to be active as a Professor of inclusive design with the ‘Royal College of Art’. His work and research is pioneering in the field of inclusive design and has shaped it extensively. One of Colemans focuses is inclusive design with regards to population ageing.

- Julia Cassim – With regards to inclusive design Ms Cassim worked with the ‘Helen Hamlyn Research Centre’ on running workshops for designers on understanding the needs of the elderly and disabled users.

- John Clarkson – As a Professor of Engineering Design Clarkson has worked as a design consultant as well as in teaching on design related fields. In particular some of his work and research centres around health care and medical equipment with regards to inclusive design.

- Helen Hamlyn Research Centre – As a department within the ‘Royal College of Art’ the ‘Helen Hamlyn Research Centre’ carries out research on inclusive design related issues. It is divided into three main research labs: Age & Ability, Health & Patient Safety, and Work & City.

Coleman, R., Clarkson, J., Dong, H. and Cassim, J. eds., 2007. Design for Inclusivity: A practical guide to Accessibility, Innovative and User-Centred Design. Hampshire: Gower Publishing; p.1 [1.]

Perrin B., n.d.. The original “Scandinavian” Normalization principle and its continuing relevance for the 1990s. In: Flynn, R. J. and Lemay R. A. eds, 1999. A Quarter Century of Normalization and Social Role Valorization: Evolution and Impact. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, Ch.8; p.181 [2.]

Perrin B., n.d.. The original “Scandinavian” Normalization principle and its continuing relevance for the 1990s. In: Flynn, R. J. and Lemay R. A. eds, 1999. A Quarter Century of Normalization and Social Role Valorization: Evolution and Impact. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, Ch.8; pp.182-183 [3.]

Perrin B., n.d.. The original “Scandinavian” Normalization principle and its continuing relevance for the 1990s. In: Flynn, R. J. and Lemay R. A. eds, 1999. A Quarter Century of Normalization and Social Role Valorization: Evolution and Impact. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, Ch.8; p.186 [4.]

See Appendix 4 for an example of his study on Microcomputers [5.]

The Design Problem – Papanek, V., 2006. Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change – 2nd edition. London: Thames & Hudson; p.57 [6.]

Papanek, V., 2006. Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change – 2nd edition. London: Thames & Hudson; pp.67-68 [7.]

Clarkson, J., Coleman, R., Keates, S. and Lebbon, C. eds, 2003. Inclusive Design: Design for the whole Population. London: Springer-Verlag; p.16 [8.]

The User Pyramid – Keates, S. and Clarkson, J., 2004. Countering design exclusion: An introduction to inclusive design. London: Springer Verlag, p.56 [9.]

Keates, S. and Clarkson J., 2004. Countering design exclusion: And introduction to inclusive design. London: Springer-Verlag; p.60 [10.]

Keates, S. and Clarkson J., 2004. Countering design exclusion: And introduction to inclusive design. London: Springer-Verlag; pp.57-59 [11.]

Keates, S. and Clarkson J., 2004. Countering design exclusion: And introduction to inclusive design. London: Springer-Verlag; p.55 [12.]

Clarkson, J., Coleman, R., Keates, S. and Lebbon, C. eds, 2003. Inclusive Design: Design for the whole Population. London: Springer-Verlag; pp.599-601 [13.]